Where History is Shared and Stories Continue

April – June 2025

Kunoopeam Netompaûog

Welcome Friends

Hello Readers. You may have noticed our newsletter’s new name. “The Runner” acknowledges and honors traditional ways of sharing news.

This quarter, we are exploring how history shapes the present through perspective and declaration. The saying, “To the victor go the spoils” holds true, as much of recorded history is written from the viewpoint of those who have won. Conquering nations establish new governments and rewrite the rules of governance to reflect their control.

This pattern is evident in American history. When the King of England ruled the early colonies, laws were written, and treaties were made—only to be broken and rewritten by colonial governments after the War for Independence. The Declaration of Independence marked the beginning of a new system of governance, shaped by the victors of that conflict.

However, to preserve history accurately, we must learn from all perspectives—those who triumphed and those who were defeated, across all socioeconomic backgrounds. History is not solely the story of the winners; it is a collection of lived experiences that deserve to be heard and understood. Only by acknowledging these diverse narratives can we gain a fuller, more truthful understanding of the past.

I encourage you to read historical documents, narratives, diaries, and journals with this in mind. While we may never fully understand or relate to the experiences of others, we should be willing to try.

~Education Team

HISTORY SHAPES OUR PRESENT…

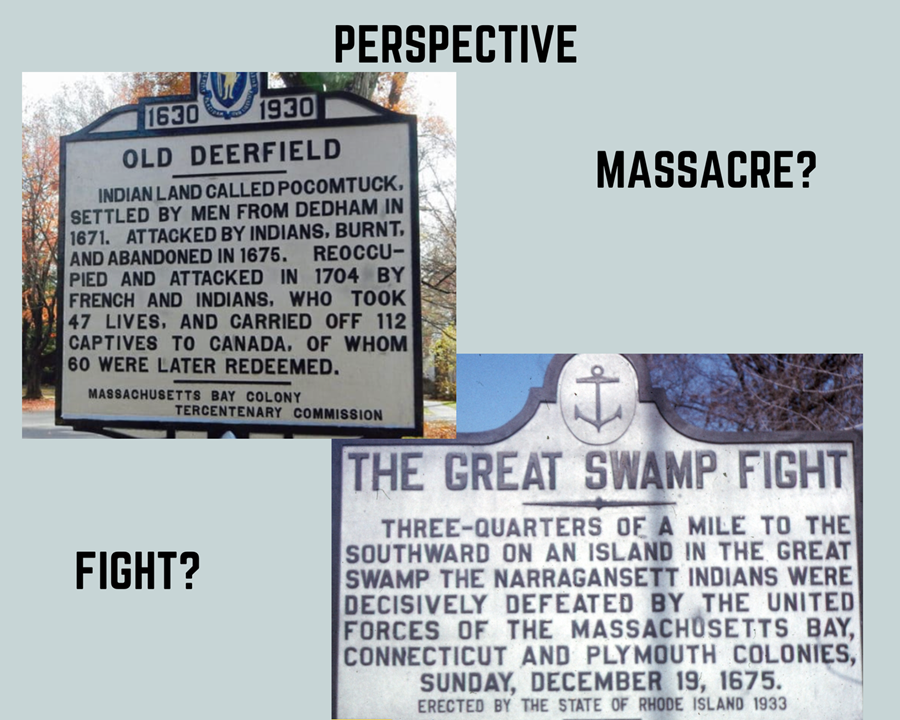

THROUGH PERSPECTIVE:

I am discouraged, disappointed, and exhausted by the perspective written on behalf of the settler-colonial people as I read the prologue of The Deerfield Massacre by James L. Swanson. The Deerfield Massacre occurred in February of 1704, when a small settlement of English inhabitants was raided by the French and warriors of five Native Tribes. In just a few pages, the author describes the Indians as barbaric, savage, and inhumane as he writes about how Native people raided the village, killing children in front of their families and committing atrocities. I am not disputing the truth of this event, but rather speaking to the profound sympathetic perspective of his opening.

I thought: It’s 1704—where are the Native people who would have been living in this area along the Connecticut River? What happened to them that this location was “available for settlement”? And why didn’t the author write about that in his opening? Still, another writer, John Demos, American Heritage Magazine (Feb/Mar 1993 Vol 44 Issue 1) described this event using these words,

“And Deerfield, Massachusetts— above all, Deerfield— scene of the region’s single, most notorious massacre.”

As I read, my mind was filled with thoughts about Deerfield and how it compares to what happened at Great Swamp in December of 1675, an event, incidentally, that occurred 29 years prior to the Deerfield event, and that we, the Narragansett people, remember as a massacre, but which has been recorded as a “fight.” This event resulted in the genocide of many hundreds of unsuspecting Narragansett children, elders, mothers, and warriors and Wampanoag refugees as they sheltered in their fortress deep in the swamp. The result of this event essentially reduced the Narragansett population drastically and many remaining men were sold into slavery throughout Caribbean islands, the Azores, and others. Another truth.

These two events, told from different perspectives, show how history is shaped by who is writing it. When Native actions are described, the language is harsh, condemning. When settler actions are described, the words soften, justify, or obscure the truth. History has been written in ways that make the Native people seem brutal while excusing or lightening the role of the settlers.

Perspective is important.

In my research, I see how history has been written in ways that justify the actions of settlers while condemning the actions of Native people. Fortunately, in recent years, more writers have begun collaborating with the descendants of Native Tribes and formerly enslaved peoples. Now, there are written histories told by Indigenous and African American voices, offering perspectives that have long been overlooked. When these authors write about historical events, the narrative shifts, as many know firsthand or have felt the lasting effects of the past through their families and communities’ experiences.

In Wandering Stars, for example, the Native perspective naturally comes through as Tommy Orange describes the Sand Creek Massacre and the generational trauma resulting. Similarly, Touch My Tears, a compilation of writings by Choctaw authors, contains stories based on family accounts of the forced removals of the Choctaw from their homelands in Mississippi, reflecting the experiences of those who endured them rather than the perspectives of those who inflicted them. These removals, endured by other Tribal Nations as well, have been called the Long Walk or the Trail of Tears.

In many books, textbooks, thesis papers, etc., the colonial accounts focus on the suffering of the settlers—the hardships they endured. But they did not ask, Who was removed from that and how were they removed in order for these lands to be settled? What happened to those Native nations—were they killed, enslaved, pushed out? Reading about the suffering of the settlers in the Deerfield Massacre made me think about the forced removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Seminole, and other Nations—how they were made to walk miles in the cold, in the middle of the night, under false promises. The telling of these histories depends on who is writing them. The difference in perspective is striking—when the history is told by those who experienced it, the story shifts.

This piece is not just about Deerfield or Great Swamp as there are so many more events. It is about how history is written—whose voices are included and whose are left out. American history, as it has long been taught, does not fully acknowledge the perspectives of all the peoples who lived these events. Indigenous nations existed long before this land was called America, yet history often reduces their presence to footnotes or a few short paragraphs in textbooks, failing to fully account for how the United States came to be—which encompasses forced removal, assimilation, and violence against Native peoples. In addition, it often fails to even teach or emphasize how the marginalized and oppressed peoples, whose life ways were forcibly altered, later adapted and contributed in powerful ways through the generations—leading to significant cultural, social, and political contributions that are often overlooked in traditional narratives. One would think America was developed solely by the descendants of early colonists, but that is far from the truth. Indigenous and African American peoples played crucial roles in shaping this country, both in the past and in the ongoing evolution of American society.

Even now, these truths are diminished, dismissed or erased. In many public schools today, we are not allowed to teach them. Events such as these and more, which are fundamental to understanding America’s past and present, have been labeled as critical race theory and are being banned. The relationships between settlers, Indigenous peoples, and the enslaved are real, documented histories—not just distant memories, but events with lasting consequences. History should not be about comfort—it should be about truth. And truth is not shaped by perspective. These truths are not easy to read or discuss, but they are truths. If history is about what actually happened, then how is it wrong to tell what has occurred and what its effects have been? The telling of history should not just come from those who wrote—it should also come from the oral and written histories of the descendants of those who lived these events, both the immigrant to these lands as well as the Indigenous. As the original inhabitants of these lands, our stories still exist, and our voices still matter.

All our futures are—and will continue to be—shaped and determined by both our past and our present.